Inventors and entrepreneurs working on hardware solutions aimed at those living in poverty—hardware pioneers—need early and sustained philanthropic support in order to bring their ideas to fruition. This is Part One in a two-part series that highlights the particular challenges faced by hardware pioneers and the ways they can be overcome.

…

Founding any new business is extremely difficult and more hard work than most people can imagine. Founding a new technology-based business is arguably tougher than that, and founding a tech hardware (rather than software) venture even tougher than that. But perhaps the toughest of all is developing and scaling a technology-based hardware venture in remote areas with scarce resources for the benefit people living in extreme poverty.

A new report from FSG, Hardware Pioneers: Harnessing the Impact Potential of Technology Entrepreneurs, funded by The Lemelson Foundation, investigates the obstacles specific to these hardware pioneers–people working on toilets, lighting, clean water and other innovations that if brought to scale could have major impact on the health, lifespan, and productivity of the world’s poor.

Hardware pioneers face a number of unique challenges: accessing prototyping equipment and capital; finding manufacturers and suppliers; and distributing and maintaining their products. As the report highlights on page 6, the target markets of hardware pioneers contribute to this difficulty, typically suffering from poor infrastructure, fragmented value chains, a hard-to-reach consumer base, and, often, weak demand for innovative, socially beneficial products. Taken together, these challenges can be called the “hardware pioneer gap”.

To address the gap and help these companies scale up, the report calls for greater levels of enterprise philanthropy—catalytic, early-stage donor funding. VentureWell has been doing enterprise philanthropy for 20 years now, providing small grants to teams of university students to develop new products (including those targeting the poor) as well as grants to institutions of higher education in the US to found courses and programs where students can learn how to be entrepreneurs. Here in Part 1 we highlight one of the ventures featured in the report, Promethean Power, which received its first funding from VentureWell. We review some of the problems the company faced in scaling and how our brand of enterprise philanthropy helped them overcome the hardware pioneer gap.

Overcoming Common Hardware Startup Obstacles: Promethean Power

Promethean Power’s story is a classic case of the challenges of being a hardware pioneer, involving huge pivots, technical and logistical problems, long delays, and lots of stops and starts. Their story begins with a supply chain issue: small, rural dairy farmers in India struggle to get the milk from their cows to market fast enough before it spoils. Big, commercial milk-chilling units in their villages would solve the problem, but require a constant energy supply often absent, and the diesel generators that could provide power are prohibitively expensive.

Promethean developed a hardware solution: the Rapid Milk Chiller, which cools milk instantly to four degrees Celsius with the help of a proprietary thermal battery. The system can chill up to 1,000 liters of milk per day even when there’s no power.

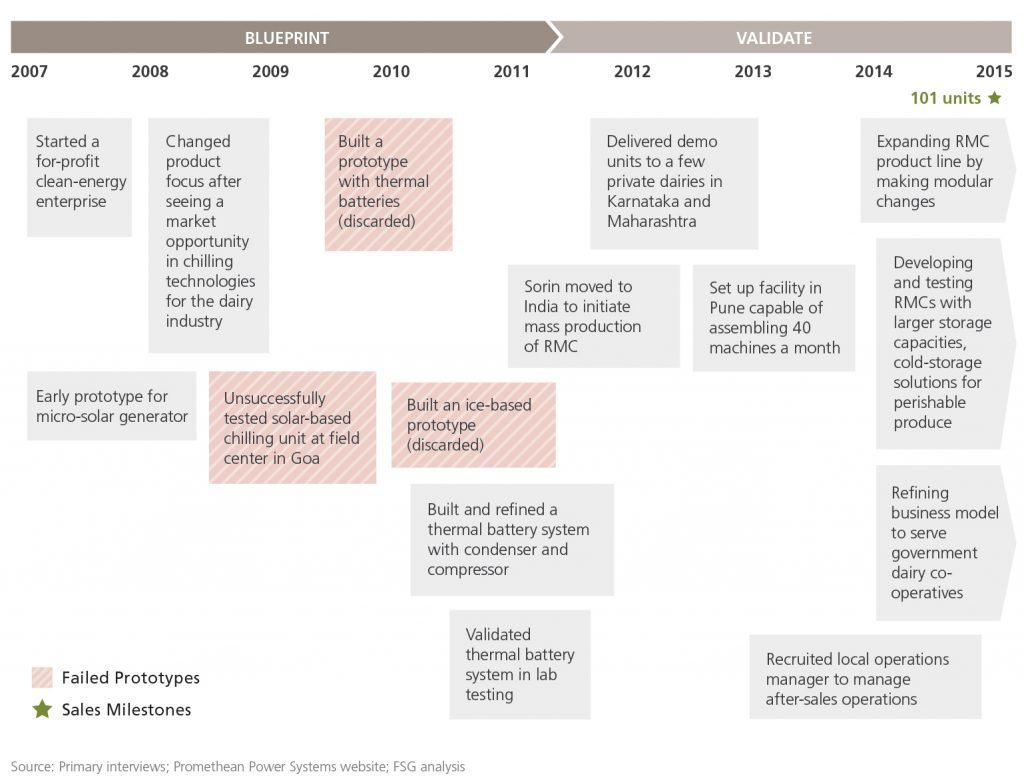

The company is experiencing success and currently growing, but it took eight years for Promethean to reach 100 units sold–from 2007 to 2015 (see Figure 1). The reasons why highlight the core challenge of hardware listed in the report: the process of developing, manufacturing, and distributing hardware requires higher development costs and longer development cycles. Without enterprise philanthropy to cover initial development, many hardware pioneers do not make it.

Figure 1: Promethean Power Systems’ Journey

The first challenge Promethean faced was getting the value proposition for the customer sorted (an issue not exclusive to hardware pioneers). The team of MIT students Sam White and Sorin Gramma started out in solar power, not milk chilling: in 2007 VentureWell gave the team a grant to develop a solar generator for off-grid communities that would meet all of a village’s commercial and residential energy needs (heating, cooling, and electricity) using auto parts and plumbing supplies.

The small grant met a central need for the team: the funding to build and refine prototypes (the developing phase for hardware pioneers). Refining the business end of the project is also key, and they used part of the seed funding to travel to India to develop partnerships and evaluate business models.

This is where things got interesting. When they got to India, according to Sorin it turned out “no one wanted our solution.” It was the age-old solution in need of a problem. They pivoted to what they discovered customers did want: the ability to chill milk.

So they had their market need. But it then took years of trial and error, prototype iteration, and shuttling between MIT and India to develop a sellable, durable, workable milk chiller–a long but important developing phase that was supported through critical funding from NSF and USAID.

Hardware done, they then needed to form a real business around it, and here VentureWell stepped in again, connecting Sam and Sorin to Villgro, a leading social enterprise incubator based in Chennai. According to this case study on Promethean, Villgro provided guidance to Sam and Sorin in a range of different areas, including initial market testing, selection of local manufacturers, building a robust supply chain, and developing an effective sales and marketing strategy. Villgro also provided critical grant funding to help Promethean produce trial units for early buyers. This is the second crucial phase, manufacturing and distributing, that often trips up hardware pioneers.

Promethean has now sold more than 200 Rapid Milk Chillers. The company has received orders from customers in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka and anticipates gaining more customers throughout Southeast Asia. They have raised more than $4 million from angel investors, venture capital funds, government grants, and private companies. But Promethean’s early development would not have been possible without the early grants, as the company found it challenging to attract interest from investors, who wanted to see a working product and a track record of sales before having serious discussions. This is where VentureWell and other enterprise philanthropists can and should come in to cover the gap.

…

Part 2 will cover the challenges faced by Greenlight Planet, a University of Illinois team that developed solar-powered lighting solutions for people living off the grid.

About the authors

Tim Binkert leads storytelling activity at VentureWell, managing the blog, the website and its content, and social media. Tim brings years of experience at VentureWell to bear in relating the stories of faculty and early stage innovators who have moved their ideas to impact through VentureWell’s programs. Tim holds a BA from Syracuse University and a Certificate in Professional Writing and Technical Communication from University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Tim Binkert leads storytelling activity at VentureWell, managing the blog, the website and its content, and social media. Tim brings years of experience at VentureWell to bear in relating the stories of faculty and early stage innovators who have moved their ideas to impact through VentureWell’s programs. Tim holds a BA from Syracuse University and a Certificate in Professional Writing and Technical Communication from University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Clinton Parks is a Washington, DC-based freelance science writer who writes for AAAS’ ScienceCareers, American Chemical Society’s Axial, and American Physical Society’s Physics Buzz, among others. He has written features, profiles and reports for AAAS’ Minority Scientists Network; written and edited articles for AAAS’ Science Careers; developed columns for SpaceNews’ “This Week in Space History”; and written case studies of the work the strategic communications firm BrandEvolve.