Inventors and entrepreneurs working on hardware solutions aimed at those living in poverty—hardware pioneers—need early and sustained philanthropic support in order to bring their ideas to fruition. This is Part II of a series highlighting the particular challenges faced by hardware pioneers. Part I featured milk-chilling company Promethean Power.

—

A new Lemelson Foundation-funded report from FSG, Hardware Pioneers: Harnessing the Impact Potential of Technology Entrepreneurs, investigates the obstacles specific to hardware pioneers—people working on toilets, lighting, clean water and other physical innovations that if brought to scale could have major impact on the health, lifespan, and productivity of the world’s poor.

Hardware pioneers face a number of unique challenges: accessing prototyping equipment and capital; finding manufacturers and suppliers; and distributing and maintaining their products. As the report highlights, the target markets of hardware pioneers contribute to this difficulty, typically suffering from poor infrastructure, fragmented value chains, a hard-to-reach consumer base, and, often, weak demand for innovative, socially beneficial products. Taken together, these challenges can be called the “hardware pioneer gap”.

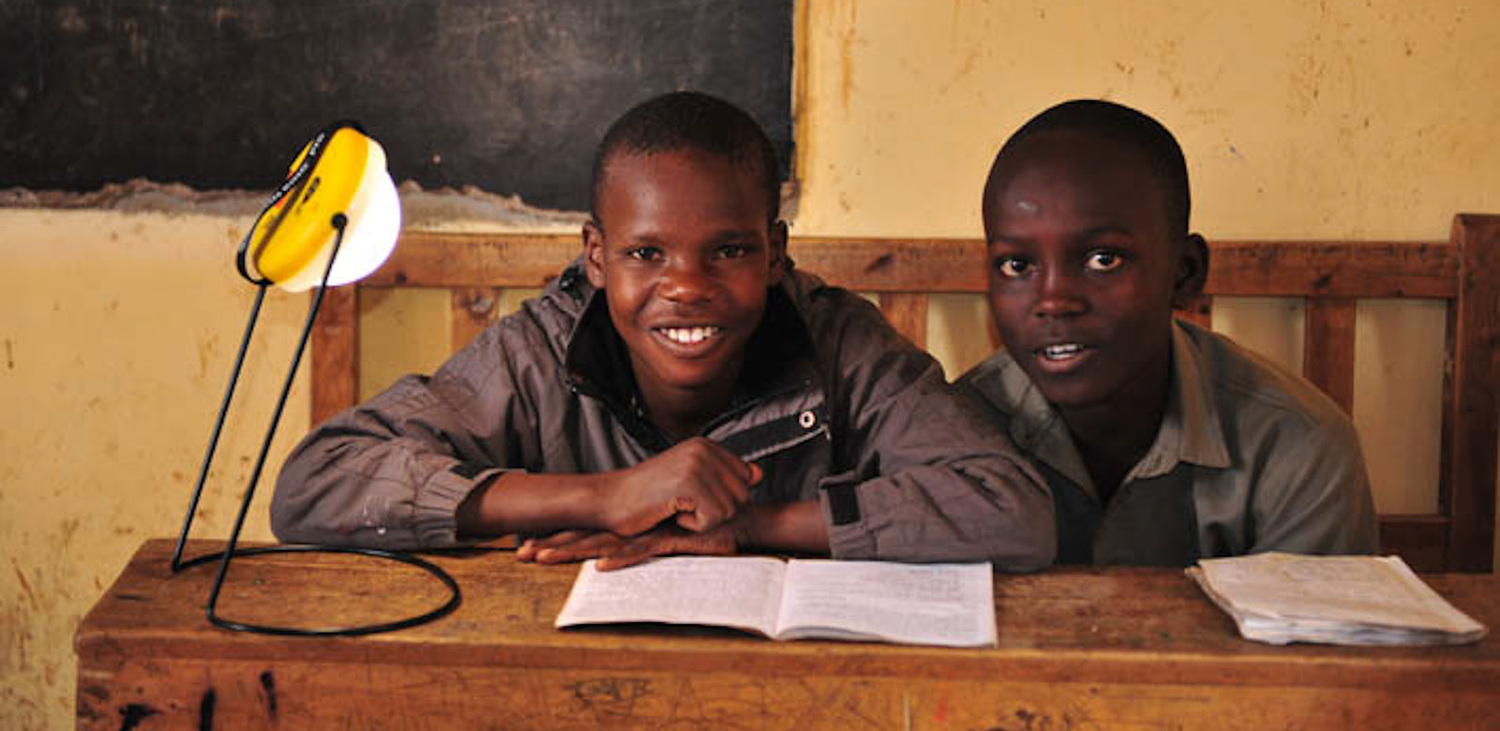

In Part II, we take a look at some of the challenges faced by Greenlight Planet, which, with the help of a VentureWell E-Team grant and mentorship from two VentureWell-funded faculty members, developed a solar-powered lantern that provides affordable and safe lighting for rural, off-grid communities.

Overcoming hardware startup obstacles: Greenlight Planet

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vqcgBPI3e84&feature=youtu.be

Greenlight Planet’s story begins when Patrick Walsh, founder and CTO, traveled with Engineers Without Borders (EWB) to install a generator in a rural Indian village. More than 1.2 billion people around the world live without access to electricity, with the majority relying on kerosene lamps as their only source of lighting at night. The kerosene exposes villagers to toxic fumes and risks burns and home fires. Over a summer Walsh and EWB set up an electricity generator for one village, but he quickly realized something: “There are over 200,000 villages in India, over half of which don’t have electricity. We weren’t any closer to solving the problem than we were before we started.”

He set out to solve the electrification problem a different way: develop a solar-powered LED lantern and form a company around it as a means of bringing it to the world. Walsh received a VentureWell E-Team Program grant in 2007 to do just that, using VentureWell funding to refine the lantern design and find manufacturing partners.

But all was not smooth sailing: Greenlight Planet faced numerous obstacles to scaling, with distribution and maintaining product quality being key inhibitors in the early stages of the venture.

Distribution

Getting new hardware products to consumers, especially those in rural areas, is a challenge. Distribution channels are often nonexistent; moving a product from production to consumer without an established retail network is extremely difficult. When no distributors are readily available companies are left to their own devices to create a proprietary distribution channel.

As the report notes, Greenlight Planet’s initial approach of setting up retail shops in India proved unsuccessful as retailers were not invested in educating customers who were new to their LED lanterns. However, the company noticed that certain agents were recruiting help in neighboring villages and selling at 10-15 times the rate of their peers. They evolved their strategy to build a network of ‘Direct to Village’ micro-entrepreneur sales agents, which met with greater success initially. In recent years, however, this model has proved difficult to replicate because of the high costs of recruiting and training motivated micro-entrepreneurs in villages.

What ended up working best for Greenlight Planet was striking up a partnership with a channel partner that already had strong reach into its target markets. Through French oil giant Total’s Access to Energy program, Greenlight was able to retail its lanterns in Total filling stations throughout Africa.

Quality control

Having overcome the distribution issue, selling four million of its lanterns to date and expanding to 11 offices in five countries, Greenlight still faces an issue: copycat versions of its hardware. As a new piece of hardware starts to build momentum in a market, it attracts attention from those looking to capitalize on the consumer interest built up by the pioneers.

These low-quality entrants can potentially destabilize the market and spoil customer trust and relations. “If anyone uses our name and sells a low-quality product, then it’s a big risk for us,” says Greenlight Planet’s Anish Thakkar.

Greenlight Planet has already had to file suits against copycat companies looking to steal their market, and have been able to successfully end threats in India. However, they still face difficulties in parts of the world that have weak patent laws.

Ultimately the lesson here is the same as with Promethean Power: Greenlight Planet’s early development would not have been possible without early grants to support prototyping and market research. This is where VentureWell and other enterprise philanthropists can and should come in to cover the gap.