From student teams to scientific and academic institutions, many recognize that complex problems are best solved when a group leverages diverse perspectives, expanding the possible solutions through multiple business, technology, design, social science, and scientific inputs. As we’ve been paying close attention to trends related to multi-disciplinary problem-solving in our field, we asked ourselves: which collaborators should be at the table when addressing big problems? And what role should faculty play in these efforts?

To help answer these questions, we’ve sought out others in the innovation and entrepreneurship community collaborating at the intersection of diverse disciplines and sectors to solve grand challenges. Jonathan Fay is the executive director at the Center for Entrepreneurship at the University of Michigan as well as the executive director for the Midwest I-Corps Node. Fay led a panel discussion during OPEN 2019 on how faculty at the University of Michigan are bringing together engineering, law, business, policy, and environmental students with industry to find opportunities to develop high-value products from captured CO2.

Dorn Carranza, director of innovation and industrial partnerships at VentureWell, spoke with Fay at OPEN about the what, why, and how of convening key =s to solve big problems. Here’s an excerpt of their conversation.

Dorn Carranza: What groups should be represented when taking a multi-disciplinary approach to problem-solving?

Jonathan Fay: I always think of multi-disciplinary teams as a four-legged stool. You need universities, industry, startups, and government entities all working together to make something happen. Take climate change—a massive issue. We need to take gigatons of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. A startup trying to do that alone? Good luck.

But as a collaborative effort, much more can be accomplished. For example, we need the startups to develop the ideas and new approaches to a solution. They can then partner with bigger companies to scale those ideas. Universities contribute research and talent to the mix. Since many of these projects aren’t viable business ideas at the beginning, government plays a role by supporting these projects with funding or other resources to take them to the next level.

Carranza: How are activities coordinated among these stakeholders?

Fay: Coordinating different players is challenging. That’s why the problem’s scope needs to be very clear at the outset. If you’re too vague, the stakeholders are not sure exactly why they’re there, but if you go narrow enough, then they’re willing to participate. You can see their level of interest in solving that problem, and that’s what you want—people who are going to put real time and money behind solving a problem that’s meaningful to them. That’s also a good Litmus test to see if you’ve got the right people around the table.

Carranza: Who do you recommend start this process?

Fay: I think universities are best positioned to start this process. It would be difficult for a big company to start it, because they’ve got competitive pressures and other logistical challenges. Startups often don’t have the bandwidth to do it, but they’d be happy to jump on and join other like-minded people that can help them. Government is constrained in what they can do on many levels. If a university president feels very strongly about something, they’ll support a faculty researcher or tech transfer office to lead the coordination process. Or you can find a dean or provost to support your efforts.

Carranza: What programs are you running at the entrepreneurship center that bring different disciplines together to solve big problems?

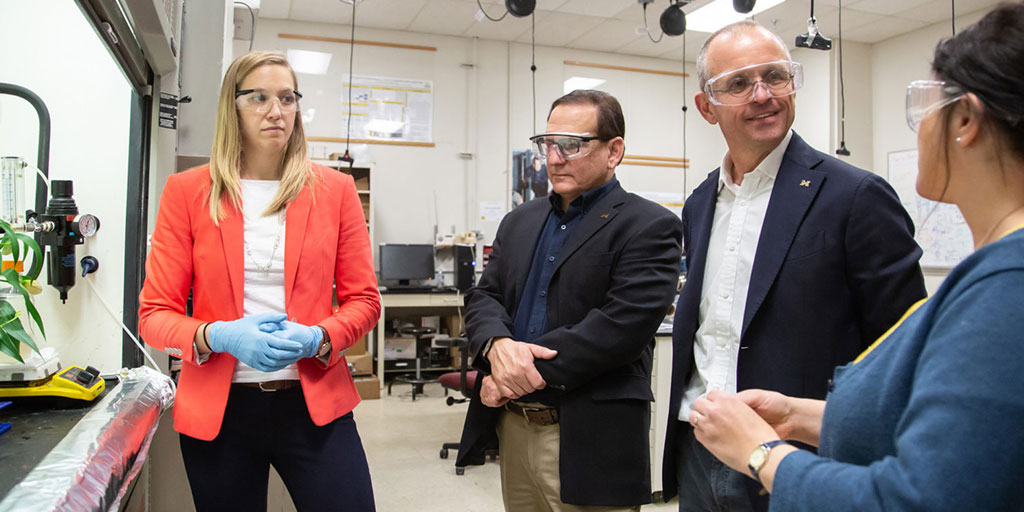

Fay: The College of Engineering as a whole just launched something called the Blue Sky Initiative, which are internal awards—up to two million per year—to bring faculty together to solve big problems. The one that our entrepreneurship center is most deeply involved with is something called the CO2 Global Initiative. We have researchers from the environmental sciences, engineering, and social sciences looking at solving this problem of climate change and the CO2 build-up in the atmosphere.

We’re also bringing together a diverse group of students that then can work with the researchers to figure out how to commercialize a discovery and actually have an impact on the world. The researchers are heads down doing the science. They don’t have the bandwidth or even inclination to take on commercialization. We’ve got some really great students from the business school, the engineering school, and the environmental sciences schools to collaborate in that effort.

Carranza: How are you engaging faculty to get involved in projects that are bringing all these different disciplines and stakeholders together?

Fay: As I mentioned, faculty contribute most of their effort on the research side. For example, one researcher is working on a new way of capturing carbon from the atmosphere, and he’s able to increase the absorbance of a certain chemical to CO2 by a factor of two. My question is: is that enough? Should it be ten? Should it be a thousand? What moves the needles? That’s where faculty can get students involved to help answer some of these questions.

Learn more about our work with the NSF Industry-University Cooperative Research Centers (IUCRC).

Photo credit: Blue Sky Initiative/Michigan Engineering