Like so many human relationships, our involvement with plastic is, well, complicated. We love it because it’s versatile, durable, and cheap. At the same time, we know we can’t go on this way—the signs of trouble are literally everywhere.

According to a 2017 study, of the 9 billion tons of plastic produced since the 1950s, nearly 7 billion tons became waste, with only a fraction recycled. Millions of tons end up in the oceans each year, a trend that, according to an Ellen MacArthur Foundation report, will result in more plastic than fish by 2050. On some Hawaiian beaches, National Geographic recently reported, the sand is now actually 15 percent plastic bits. Just how this microplastic is impacting the food chain—and us—is a topic of ongoing research. And still we can’t quit you, plastic: globally we buy 20,000 plastic bottles every second.

Can this relationship be saved? The following VentureWell-supported innovators think so. They’ve been taking on the problem from a multitude of angles: Reimagining the garbage can, developing chemical processes that separate reusable polyester from old clothing, and bringing greater efficiency to the often-wasteful process of plastic manufacturing.

Trash Can 2.0

Standing before public waste bins marked Recyclables and Trash, most of us think we know what goes where. The TrashBot is here because, too often, we are wrong.

“Humans on average get sorting correct about 30 percent of the time,” explains Charles Yhap, CEO of CleanRobotics, the three-year-old Pittsburgh-based startup that makes the trash-separating garbage can. “That’s statistically worse than guessing.” By comparison, the TrashBot, which uses sensors, robotics, and artificial intelligence to identify and sort items, is correct 90 percent of the time, a figure CleanRobotics hopes to bump even higher.

Now in small batch production, TrashBots have been tested at Pittsburgh International Airport and other local high traffic areas, and have been bought by customers in North Carolina, Washington state, and Australia, with a number of potentially game-changing orders in the works, Yhap says. While priced comparably to other high-end commercial containers (which run between $1,200 and $3,500), they can save customers money by generating detailed trash data, eliminating the need for expensive waste audits.

But it’s the TrashBots’ sorting abilities that have made them a timely development, especially in the wake of China’s recent decision not to accept further imported recyclables beginning this year. “The recycling industry is really optimized for speed and volume,” explains VP of Engineering Tanner Cook. “Now that the market in China has all but dried up, they have to start thinking about the quality of their output as well. What we are finding is that a lot of recyclers and waste managers are looking for a way to clean up their stream upfront, and we are very much a natural part of that story.”

We humans might do a better job recycling if we didn’t have to contend with rules that vary widely by region and with materials that we think should be recyclable but simply aren’t. (TrashBots know the difference.) We also try to recycle containers that are not entirely empty, which causes problems at materials recovery facilities. (TrashBots dump out any liquids.) Those kinds of errors explain in part why only 20 percent of what’s put in a recycling bin actually gets recycled, says Cook.

TrashBots may offer help here as well. The devices have screens that can be used for educational messaging, allowing TrashBots in public spaces to serve as recycling coaches, teaching us humans how to recycle right so we can take that knowledge home with us.

Spinning New Fabric from Old

Polyester—the petroleum-based plastic that made possible fleece jackets, skin-tight fitness apparel, and John Travolta’s Saturday Night Fever disco suit—is now the most common material used in clothing, eclipsing even cotton, and one of the world’s most-produced plastics. Until Ambercycle came along, it could not be easily recycled.

“Right now, all of this material in some form ends up in the landfill or the ocean,” notes CEO Akshay Sethi. “There’s no way to close the loop. Anything that you read about microfibers or microplastics in the oceans, all are pretty directly linked to clothing.”

Sethi’s three-year-old startup is working to change that, using chemical catalysts to tease the polyester fibers out of fabric blends so they can be reused in new textiles. At their newly opened 15,000-square-foot research facility and pilot plant in Los Angeles, Ambercycle’s ten-person team puts discarded clothing through a three-step reaction process to produce a ton of reusable polyester every day, which is being marketed under the trade name Moral Fiber. Unlike heat-based processes now used to recycle polyester, the polymer is not degraded. “We are just cleaning away the additives, dyes, dirt, and other polymers around it,” Sethi explains. “When we recover that material, it’s nice and clean. You would not be able to tell the difference between this and one that came from oil.” The cotton waste is now sent to an anaerobic digester, where microbes break down the cellulose to produce biogas for energy, but may someday be reused as well.

Because just 5 percent of Ambercycle’s costs are raw materials—compared with 95 percent for petroleum-based polyester—the process costs as much as 40 percent less than conventional manufacturing methods, Sethi says. It’s also environmentally friendly, using only non-toxic chemicals that are themselves recycled.

Most promising of all, Sethi says the process could be applied to other materials beyond fabrics. “We foresee bottles, we foresee packaging,” he says. “Any material that contains some plastic can be given a second life.” The company, which recently raised $2.5 million in funding, is exploring building larger plants that can process even more discarded clothing. “I’d like to build a 100-ton-per-day plant,” says Sethi, “and eventually make all the clothing that we wear from post-consumer material.”

Rethinking Nylon

Plastic waste may get the headlines these days, but plastic manufacturing has been raising sustainability issues for years. Take nylon 6,6. You may not know it by that name, but it’s in products all around you: carpets, engine parts, those handy zip ties. Each year the chemical industry produces millions of tons of it, but even that is not enough to keep up with demand. The bottleneck is a shortage of a key chemical used in the production process, adiponitrile (ADN), which for the past half century has been manufactured using processes that are both resource and energy intensive.

Sunthetics, a startup co-founded by two New York University chemical engineers, has developed a more efficient production method for ADN that uses less of the non-renewable raw materials and can be powered by solar electricity, decreasing the carbon footprint. While the process is also more cost-efficient— by 30 percent—saving money is just one of the team’s goals. “We are part of a new generation of chemical engineers where improving cost and efficiency is not really enough,” says Myriam Sbeiti, who, with Daniela Blanco, co-founded Sunthetics in 2017. “What we need to do is improve sustainability.”

Two methods are now used for manufacturing ADN—one uses heat, one electricity—and both are environmentally problematic. “These reactions in industry haven’t been updated in years,” explains Blanco, whose Ph.D. project was the basis for Sunthetics. “The thermal process is very dangerous and uses many toxic chemicals. The process that uses electricity is not efficient enough. That’s what we decided to change.” Sunthetics solar-powered electrochemical process nearly doubles the production rate while reducing carbon emissions by 20 percent. They’ve been able to demonstrate the technology at a lab scale, producing small amounts. “What we need to do is to take the model further and prove the concept at a larger scale,” says Sbeiti.

Sunthetics has had conversations with companies who might be interested in more sustainably produced nylon, such as manufacturers of outdoor apparel, but may choose to license its technology to other companies rather than try to compete with industry giants. In either case, they hope their discoveries can help bring change to an industry where sustainability has not been a top priority. “The chemical industry needs to keep growing, but it also needs to grow in a responsible way,” says Blanco. “And that’s what we are trying to do—to influence the way they work so it is not just efficient and profitable, but also environmentally responsible.”

The entrepreneurs behind CleanRobotics, Ambercycle, and Sunthetics see the challenges posed by plastics as a great opportunity, a chance to reverse our unsustainable habits and help usher in what some are calling the new plastics economy. And while the challenges of resolving a global problem so many years in the making can seem overwhelming, these innovators have an inspiring message: solutions do indeed exist, and—with support and resources—could soon be making a difference.

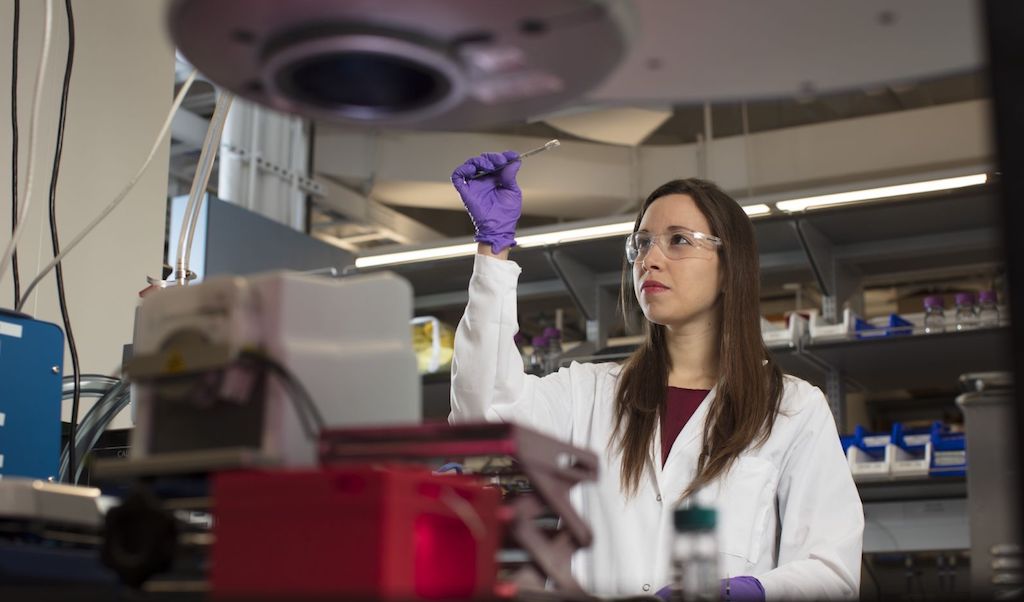

Photo credit: Office of Graduate Admissions at NYU Tandon School of Engineering. Daniela Blanco of Sunthetics is analyzing components for electrochemical devices at the Multifunctional Material Systems Laboratory at NYU.