As entrepreneurship educators, we’re fortunate to work with bright and innovative students, forward-thinking colleagues, and institutions supporting programs that respond to market and economic demand. But despite all of these attractive ingredients, we encounter challenges on a regular basis. The more new things we try, the greater the probability of experiencing failures, flops, and a multitude of frustrations: new courses that aren’t as subscribed as we had hoped, cross-campus programs that don’t produce the level of interest needed to justify the investment of time and money, and creative spaces of innovation that are underutilized.

We teach our students that learning from mistakes allows them to propel new products and services forward. The same is true for entrepreneurship educators: we evolve our offerings based on our failures, flops and frustrations. It’s important that we share these experiences with colleagues. Organizations like VentureWell, with which I have been affiliated since 2003, provide the community to learn from one another.

Without further ado, here are three lessons from my personal “failure resume” as an entrepreneurship educator:

A failure that inspired a tiered approach

In launching the Juniata College Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership $500,000 Student Seed Capital Fund in 2003, we were excited to offer undergraduate students access to seed capital in the form of a convertible note. It was a chance to secure “big” startup money for “big” innovative ideas. As we anxiously waited for dozens of applications to flood our inboxes, something unexpected happened: students came in expressing hesitancy, doubt, and concern. They weren’t ready for the “big” money; what they needed were some low-risk resources to vet their portfolio of initial ideas, which, after some grooming, could form the basis of a formal seed capital application.

How did we respond? We created and offered the highly popular “First Step” program, which included a small grant, credit for space in the Bob and Eileen Sill Business Incubator, and a stipend for time spent on the development of business concepts. VentureWell took a similar approach, as they recently evolved from the “all or nothing” E-Team grants to the current three-staged model.

Lesson learned: When introducing an entrepreneurship support program to students, provide stepping stones to decrease the barrier to entry.

A flop that eventually flipped

When I arrived at the University of Pittsburgh’s Institute for Entrepreneurial Excellence in 2008, the campus-wide business idea competition had a few thousand dollars of prize money in hand. There was definitely room for growth and, with that in mind, potential sponsors and donors were approached. While many said “yes,” pushing the total prize money upwards of $20,000, a few potential sponsors responded with a disappointing “no.” We decided to invite those who declined financial participation to attend the competition and engage with student winners. Through continued relationship-building efforts, these individuals and organizations not only came on board as donors, but gradually escalated their contributions. The Randall Family Big Idea Competition, as it is now called, currently awards $100,000 in prize money each year.

Lesson learned: Turn initial “no” answers into opportunities, because converts often become your biggest supporters.

A frustration that led to evolution in the curriculum

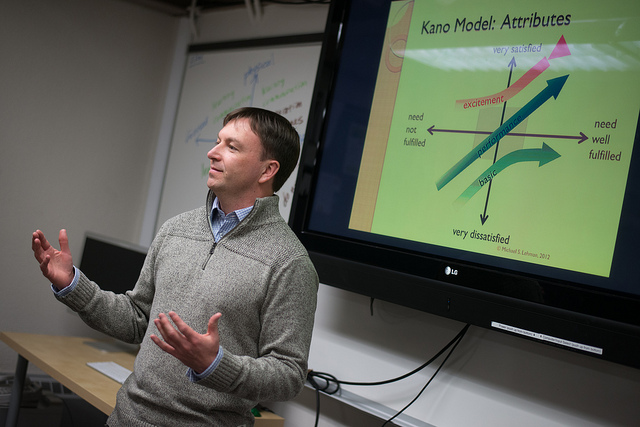

As members of the faculty team launching the M. Eng. in Technical Entrepreneurship at Lehigh University, my colleagues and I had the opportunity to craft the curriculum for a 12-course sequence. Our graduate students provided positive feedback as they launched companies, joined startups, and innovated as intrapreneurs in corporations. However, the final project courses, delivered over a six-week week summer session in 2016, didn’t convey the exciting accelerator-like, culminating capstone experience we had imagined. So in 2017, the faculty team applied creativity techniques, pedagogical experiences, and industry connections to turn the frustrations into a new model for an entrepreneurship project course. (It should be noted that VentureWell’s Faculty Grants provide support for educators in taking their pedagogy to the next level.)

Lesson learned: Don’t forget to pull out your team’s collective toolkit of experience to build upon existing curriculum.

As professionals working in higher education—and entrepreneurship—the chances are high that we won’t always get it right the first time around. We need to be better at sharing our mistakes—those unanticipated failures, those unbelievable flops, and those countless frustrations—as opposed to focusing solely on what’s worked. This “failure collaboration” will allow us to learn from one another and, collectively, move the entire field of entrepreneurship forward.

The author led an OPEN Exchange session titled “Failures, Flops and Frustrations” at the VentureWell annual OPEN conference on March 24, 2017 in Washington, D.C.

About the author

Mike Lehman works at the intersection of entrepreneurship, science, and higher education. Lehman is a Professor of Practice at Lehigh University, where he co-developed and teaches in the Master’s of Engineering in Technical Entrepreneurship. Prior to joining the faculty at Lehigh, Dr. Lehman developed and grew programs at the Institute for Entrepreneurial Excellence at the University of Pittsburgh. Earlier in his career, he served as the founding director of the Juniata College Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership. Lehman holds a BS from Juniata College, an MD from the Penn State College of Medicine and an MBA from the Leeds University of Business School in England.